Longread

The holy grail of eel propagation

'Closing the cycle': that's the big goal. If it would be possible to reproduce eels in captivity, the eel could be cultured and the pressure on the wild population alleviated. Researchers are getting closer step by step, but the step from larva to glass eel is still eluding them.

How do you breed fish whose life cycle involves a reproductive migration of thousands of kilometres from the European continent to the other side of the Atlantic Ocean? And which then, after hatching somewhere in the depths of the Sargasso Sea, undergo a metamorphosis during the months when they swim back to Europe? Decades of research on this phenomenon have been conducted by various groups all around the world, including by Wageningen University & Research.

On the Wageningen campus, most of the stages of the eel can now be observed, each in its own tank. The eggs, which have never been found in the ocean, are obtained in the experimental facilities through hormone treatment and artificial insemination of adult eels. The pre-larvae and the leptocephalus larvae they grow into. And the glass eels, which can be successfully raised into adult, sexually mature eels.

But one step in the cycle still eludes researchers: the transition from larva to glass eel. “So far, no one has been able to accomplish the metamorphosis of leptocephalus larvae from the European eel into glass eels in captivity,” says Arjan Palstra, senior researcher of the Animal Breeding and Genomics group at Wageningen University & Research. In the wild, that mysterious metamorphosis takes place somewhere in the ocean, unseen by humans, just before the glass eels reach European shores. That means that all the glass eels in the Wageningen nursery come from the wild. “The step from larva to glass eel is the gap in the cycle that we have yet to close. Once we have established the production of glass eels, we have already developed a procedure to raise them into broodstock eels.”

That is commercially interesting, and may make it possible to introduce glass eels into the wild to contribute to the recovery of the population.

Sea bass as a surrogate mother?

What makes the research so challenging is that there is no 'natural reference'. “There is still a lot we don't know about the sexual maturation of eels and what happens to them in the ocean in that respect,” says Palstra. “Everything we know comes from artificial reproduction. But we want the breeding of eels to be as natural as possible. That means triggering the natural mechanisms of the eels and then allowing them to mature spontaneously.”

We want the breeding of eels to be as natural as possible

Despite all these challenges, steady progress is being made. “All our eels mature and we manage to get 75 percent of the females to lay eggs which produce thousands of healthy larvae. As a result of improvements in the hatchery conditions and larval diets, we are keeping more and more larvae alive for increasingly longer periods.”

Female eels are injected with hormones to trigger ovulation and sexual maturation. “In the wild, eels become sexually mature during or after their long migration through the ocean, but in a farm we have to artificially trigger that,” says Pauline Jéhannet, a research associate at Animal Breeding and Genomics and at the Centre for Genetic Resources at Wageningen University & Research. “We are working on alternatives for these injections, such as a subcutaneous implant that delivers the hormones slowly over time.”

It is conceivable that we introduce eel germ cells to another fish species, as a type of surrogacy for eel eggs

Jéhannet is mainly working on freezing eel sperm, in the future possibly also eggs and embryos. “It is conceivable that we introduce eel germ cells to another fish species, such as the sea bass. As a type of surrogacy for eel eggs. If we can freeze seed without loss of quality, we can maintain a stockpile without having to treat adult males every time.”

The same thinking lies behind the recently launched research into organoids, artificially grown miniature organs of eels. Jéhannet: “Think of the liver, ovaries or the pituitary gland, a hormone-producing gland under the brain. With such organoids, we can scale up nutrition research or hormone research, for example, without the need for more laboratory animals.”

Aqua gym for eels

Palstra describes eel farming and related research as a continuous 'improvement programme'. “The way we are achieving results now is not yet the optimal way. You would rather have eels that you don't have to inject weekly. And no larvae that need to be fed manually all the time, which is currently as much as five times a day. This is all still too intensive for commercial breeding, for example, so we still need to take steps there.”

A simulated migration can help trigger the eels to enter puberty

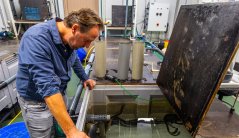

A natural element of the eel's life that is missing in the nursery is obviously migration. A simulated migration can help trigger the eels to enter puberty. The eels are therefore kept in a swimming flume where they can swim against an artificially generated current for months. “Like an aqua gym for fish. We can adjust the temperature of the water to mimic the conditions they would encounter during migration in different parts and at different depths of the ocean.”

Palstra and Jéhannet are optimistic that the cycle can soon be closed and the 'holy grail' of truly cultured eels will be achieved. Research has gained momentum with several breakthroughs in recent years.

Palstra: “In 2019, a 43-year-old eel in a Finnish aquarium spontaneously became sexually mature, so without any hormonal injections. We now visit that aquarium every year to examine that group of old eels: blood samples, hormone measurements, ultrasound. We don't have a natural reference, but this is the nearest thing we have.”

Sharing knowledge

Another breakthrough: the cycle has already been closed for the Japanese eel. “Japanese researchers have now been able to raise the seventh generation of eels. Currently, they are trying to perfect the process to reduce costs and enable commercial production.”

What is the secret of the Japanese approach and could it work for European eels too? “We know much more about the Japanese eel. Their exact spawning spot has been found. The migration distance of that species is shorter and their route has been completely mapped. But not all information can always be shared among eel researchers, often there are restrictions. Governments and investors are also involved and it’s obviously of great economic interest. We will soon be organising a training session for European researchers in Japan to transfer knowledge faster and more efficiently.”

Despite these economic interests, national and international cooperation is crucial in this first phase of eel propagation. In 2016, the Eel Reproduction Innovation Centre (EELRIC) was established, in which Duurzame Palingsector Nederland (DUPAN) collaborates with Wageningen Livestock Research. One of EELRIC's goals is to establish a global network to share knowledge. Wageningen also works according to a kind of 'open source' method. Palstra: “We share all our knowledge. The important thing is that someone manages to close the cycle, but we don’t necessarily have to be the ones who will do it.”

In this regard, cooperation within the Wageningen Eel Project Group, of which Palstra is the chair, is also crucial. It is precisely because we lack that natural reference that it is so important that we have colleagues like Ben Griffioen and Reindert Nijland who could raise more information on the reproductive migration of the European eel. We really need the results of the bio-sensing boxes and sensors they use. We will only manage to raise eels if we all work together.”